Reflection by Elizabeth Palmer, Chief Executive of St Vincent de Paul Society (England & Wales)

"Refugees are mothers, fathers, sisters, brothers, children, with the same hopes and ambitions as us - except that a twist of fate has bound their lives to a global refugee crisis on an unprecedented scale.”

That quote from critically acclaimed writer and humanitarian Khaled Hosseini elegantly describes the condition and plight of asylum seekers. We all share the same needs and aspirations, which is why we should seek to influence the way in which we, as a nation, treat people looking for sanctuary on our shores.

Home Secretary Priti Patel is planning to enshrine the government’s New Plan for Immigration (NPFI) into UK law following an unusually brief six-week consultation period which has just ended. The ‘streamlined’ NPFI will create a system in which the way people enter the UK will impact how their asylum claim is processed and the status they might receive.

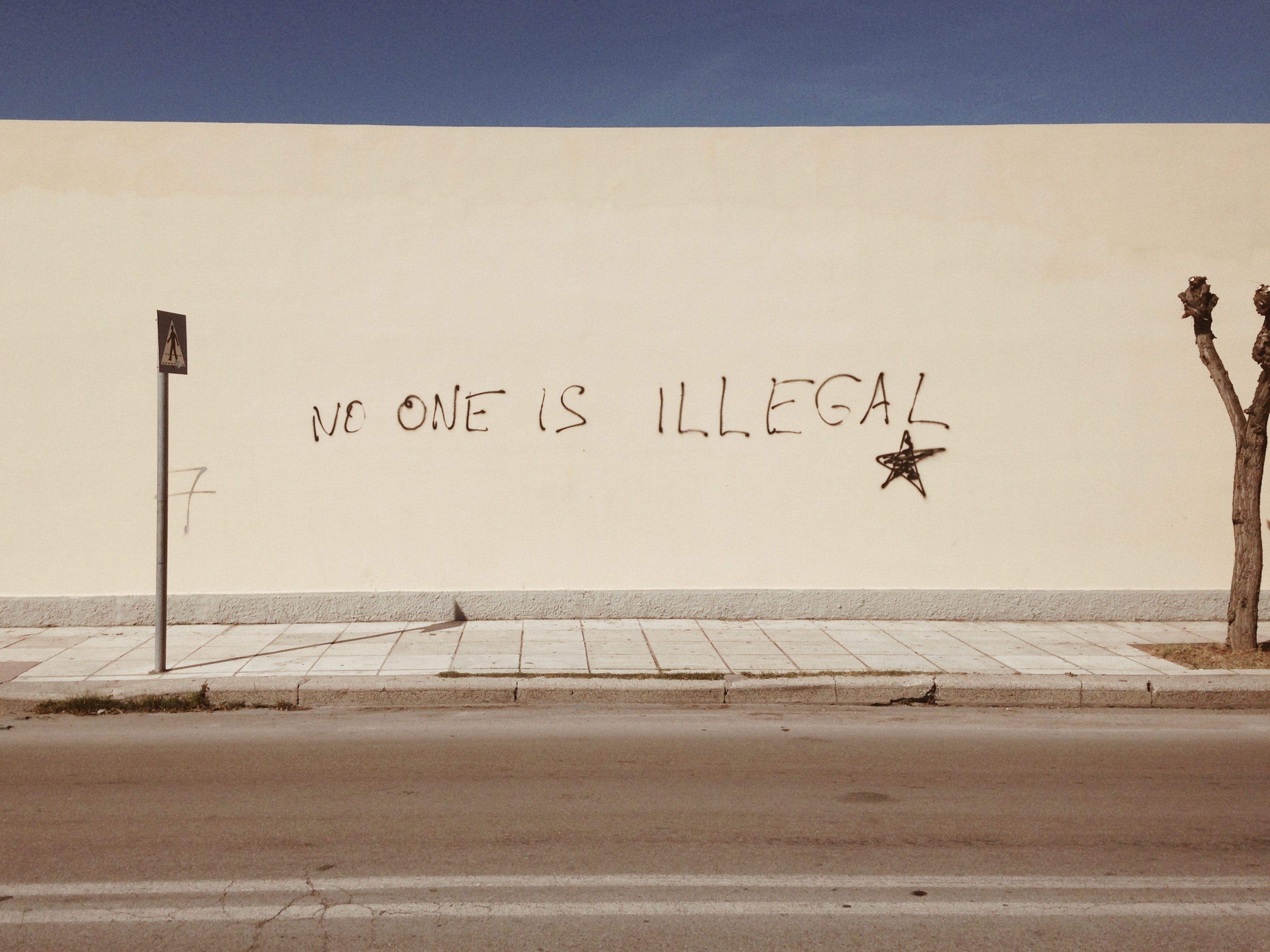

Should the NPFI proposals be signed into law, undocumented entry to the UK will be criminalised and those falling foul of the new legislation penalised. In practice, this will mean it will effectively be impossible for most people to claim asylum here because “safe and legal” routes for claiming asylum in the UK are extremely limited due to the UK’s island geography and “acceptable” routes under NPFI proposals could never feasibly be made available to all who need them.

A system which criminalises people for seeking sanctuary seems perverse. In a modern and enlightened society the dignity and humanity of the individual should be at the heart of the NPFI, any other driving principle ignores the manifold benefits of welcoming refugees to our country and risks creating a divisive culture in our communities.

It’s natural to care

In the light of research from the Max Planck Institute in Germany, and studies carried out at the University of Chicago and the University of California, there is a growing body of evidence that our primal instinct isn’t self-preservation, but is, in fact, compassion, which can be defined as an authentic desire to help when we perceive suffering.

For people who have been forced to leave their home, often after witnessing their communities and families being ripped apart by conflict or economic deprivation and being left with no option but to undertake a perilous journey to a foreign country in the slim hope of finding sanctuary, their suffering is all too evident. Our compassionate response to that must be as unequivocal as it is in our nature to provide.

Our government should treat asylum seekers with dignity, which means addressing their problems as individuals. We cannot neatly package asylum seekers under a single banner; each person’s situation is different, and a streamlined NPFI will never be flexible enough to assess and address the complexity of their issues.

Similarly, a one-size-fits-all system which places more weight on the mode of transport and the route taken to our shores than the driving force behind the need for the journey, cannot be the best solution. According to writer and poet Warsan Shire: “No one puts their children in a boat unless the water is safer than the land.”

Climbing into a vessel which offers hope, but which can all to quickly become a carrier of death, is the last resort for many asylum seekers. Knowing this strengthens our bond. The government, as our representative body on the international stage, should embed principles of welcome, protection and integration into its policies. We should treat individuals and families seeking sanctuary on our shores as our brothers and sisters and valued members of our communities.

To fail to accord those seeking asylum with dignity only fosters discontent and fear. It fails to recognise the benefits of welcoming migrants into our communities.

Diversity makes us stronger

The UK owes much to refugees who have made their home here. Among the thousands in the public domain who have enriched our country, Judith Kerr, the author of family favourite children’s book The Tiger Who Came to Tea, fled Nazi Germany when her father openly opposed the Third Reich. In business, Michael Marks, one half of the famous Marks & Spencer brand, was a Jewish refugee from eastern Europe, while Sir Montague Burton, founder of the Burton retail chain, was a refugee from Lithuania. In the performing arts, late Queen frontman Freddie Mercury came to England from Zanzibar in 1964, comedian and actor Omid Djalili was born to Iranian refugee parents, and singer Rita Ora came to the UK as a refugee from Kosovo while an infant.

However, it’s in cities, towns and villages across the nation where cultural diversity brought about through migrant integration ensures our communities are vibrant and invigorated. The meeting of different cultures, cuisines and attitudes is anchored by the things we share in common - family, community and faith.

The government’s NPFI should offer asylum seekers the opportunity to integrate through language, sharing cultures and by offering the means to participate in community life. Diversity is the lifeblood of our communities, but it can only flourish if individuals and families are supported by a structure which enshrines welcome and protection as a building block of legislation.

Have faith in the human spirit

Albert Einstein, one of the most influential thinkers in history, and a refugee from Adolf Hitler’s Nazi regime, once said: “The world will not be destroyed by those who do evil, but by those who watch them without doing anything.”

We cannot be silent witnesses to the passing of legislation which treats vulnerable individuals as bureaucratic pieces in a game of global chess. We should be proactive in our approach.

The refugee crisis sweeping the western world requires faiths to come together under one ideal to ensure asylum seekers receive the justice they deserve. Christian, Muslim, Hindu, Sikh, Jewish, Buddhist and all other faiths should unite in a common bond to ensure the UK’s immigration laws are fair to all who seek entry. It is right that legislation should punish those who seek to profit from the suffering of refugees, however the system should treat those seeking sanctuary as human beings, individuals with aspirations of freedom, and not a potential drain on resources.

The concept of sanctuary is far more than merely being on safe ground; for those seeking asylum, safety it is about community, family, work and not being isolated. It is about being free to conduct your life in a manner of your own choosing. Safety is not a country; it is an innate sense of belonging and well-being, which is the essence of being human.

The NPFI is an opportunity to show the world we are a compassionate nation which undertakes with humanity its obligations to anyone seeking sanctuary on our shores. Detention, mistrust and the weight of bureaucracy haven’t worked, so perhaps the hand of friendship and understanding might offer a more equitable solution to the refugee crisis.